In the world of financial media–it is a full court press for your attention (read: your dollars). Yet it always strikes me very odd to see way too many people worship random financial dogma or slick talking market gurus.

Many clearly see market gurus as religious prophets. When CNBC zombies say it’s time to buy Google or dump Las Vegas Sands, many follow random advice blindly–mostly because of the name fame factor. Do you actually know anything real about these people? Or could they just be cartoons? Is CNBC Credible?

If fame is a factor in your market choices—honk the horn and yell, “Booyah!” So why do people listen to talking heads making predictions all day long? Are they thinking, “Maybe he will help me make millions in the stock market?” Or is it, “Maybe he’s right in his Google timing, and I can make a killing right now?” Or is it really, “He’s on CNBC; he has to be right!”

Think of it this way: A guru comes on and says buy Gold. Isn’t he saying that to the whole world? Worse yet, if you allow yourself to buy on a guru tip, does he call you up when it’s time to sell? Or are you just assuming when he says buy, Gold will go up forever and you’ll never need to sell?

Visit to CNBC Offices

I have had several odd CNBC experiences over the last 15 years.

Odd.

Just damn odd.

From Maria Bartiromo (see video below) to David Faber to Joe Kernen to Susan Krakower… what follows is my CNBC experience.

However, first consider an instantly recognizable passage for Seinfeld comedy fans:

NBC Executive: I just wanted to let you know that we’ve been discussing you at some of our meetings and we’d be very interested in doing something.

Jerry: Really? Wow.

NBC Executive: If you have any idea for a TV show for yourself, well, we’d just love to talk about it.

Jerry: I’d be very interested in something like that.

NBC Executive: Well, why don’t you give us a call and maybe we can develop a series.

Jerry: Okay. Great. Thanks.

George returns.

George: What was that all about?

Jerry: They said they were interested in me.

George: For what?

Jerry: A TV show.

George: Your own show?

Later Jerry and George are talking.

Jerry: Well, what’s our new show idea going to be about?

George: It’s about nothing.

Jerry: No story?

George: No, forget the story.

Jerry: You’ve got to have a story.

A little later.

Jerry: And its about nothing?

George: Absolutely nothing.

Jerry: So you’re saying, I go in to NBC, and tell them I got this idea for a show about nothing?

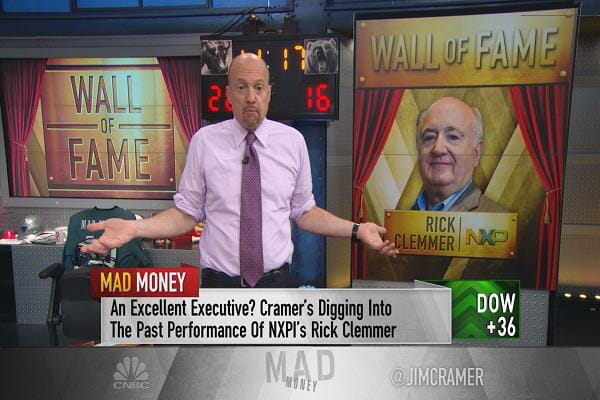

Just like Jerry and George CNBC (owned by NBC) once invited me to their offices. They paid my travel. I had no specific knowledge of what they wanted, but the meeting was with producer Susan Krakower who had invented Jim Cramer’s show Mad Money. It was assumed that they were looking for new content. Once there, the meeting was in a small windowless New Jersey office with Krakower and her two lieutenants. It was like when Jerry and George went to meet with NBC. A Jim Cramer poster hung behind her (no joke).

Krakower sat in front of me behind a large desk and her two lieutenants flanked me on either side. It was triangulation so to speak. They peppered me with small talk questions, yet seemed to have no clue about my writings, research, or thinking. They had not read my books. They only had a picture of me that I had not seen before (something you might imagine an actor brings to a Hollywood casting call). This was the epicenter of CNBC’s content development: A glossy headshot.

Krakower asked me to hypothetically program ten hours of airtime for CNBC. My idea for new programming was blunt: trend following, not more stories. My ability to play the game was not very good, and it was easy to see that candor was taken as an insult. The conversation bounced around for 30 minutes and surprise, surprise there was no further dialogue.

Walking through the halls of CNBC’s studios that day reminded me of The Truman Show: a constructed reality, a staged, scripted TV show. Except instead of it being one person (Jim Carrey’s character in The Truman Show) who does not know reality is fake, CNBC’s reality plays to a worldwide audience daily, week after week and year after year. Views like that make me a persona non grata with some.

Once after speaking to an audience of nearly 1,000 in Brazil, and after the audience had just listened to me proselytize (come on, I got to play the title of this book up some!) about the negatives of media and press, the barbed wire question was thrown to rip me a new one:

“How are you different than Jim Cramer?”

Now that question came after an hour of talking about trend following in depth in the context of the 2008 market crash as trend followers cleaned up. But still, it was a great question to explain further. It comes down to fundamentals versus trend following. If you watch Cramer, you always have to tune in to stay current, that is the hook. That is not the trend following process. It is not my process.

Once you know the trend trading way, you do not need anyone to hold your hand to cross the street. That’s a big difference. Although, teaching as many people as possible is my goal, and capitalism courses through my veins, comparisons to Cramer do not equate. My logic does not win everyone over. One reader complained:

“You trash CNBC and other people, but they provide very good information if you know how to use it, and you shouldn’t just trash everybody’s point of view because there are a lot of smarter people than you, who have a better opinion.”

He is so lost.

Joe Kernen and David Harding

On April 8, 2011, CNBC anchor Joe Kernen interviewed David Harding. At the time of that interview, Harding’s firm Winton Capital was managing $21 billion dollars in assets for clients via trend following strategies. Consider Kernen’s interview and my questions that follow.

Joe Kernen started the interview reading from a piece of paper that described Harding as a systematic trend follower who believes scientific research will succeed in the long run. He wondered out loud if “computers” were used and asked Harding to describe his trading strategy.2

Harding, on remote from London, responded that his firm “goes with the flow.” He follows trends and makes money going long on rising markets and short on declining markets. He mentioned that there had been enough trends for his firm to make money nearly every year for the last 15 years.3

Kernen pounced, wondering whether he could blame Harding and other trend followers for Oil and Gold going higher and “for the pendulum swinging much further than it should on a fundamental basis.”4

Harding thought there might be some truth to Kernen’s point, but there was only so much time to elaborate. Kernen, under his breath, with a huge wide smile emerging, interjected at that acknowledgement: “Uh, yeah.”5

Harding reminded Kernen that his firm was limited by speculative position limits set by the government and that his trading size was tiny by comparison to major investment banks. Harding went on to further clarify that he doesn’t trade by a “gut feel.” He added: “We don’t just make it up.” He also didn’t apologize for his scientific approach to markets, an approach he defined as “rigorous.”6

Kernen replied with a shot across the bow bringing up failed hedge fund Long Term Capital Management (LTCM). He saw it as ironic that LTCM folded in the same year (1997) that Harding’s firm launched: “I heard science and I heard you’ve never had a down year, and it just reminded me of LTCM.” Kernen talked sarcastically about the Nobel Prize winners at LTCM, their “algorithms,” and the fact that they never had a down year until their blowup.8

Harding quickly clarified that his firm did have a down year in 2009 and that his performance success actually went back over two decades—23 years to be exact. He noted that his first firm AHL (which he sold) was now the world’s largest managed futures fund. He also addressed LTCM head-on, stating that the book When Genius Failed (the story of LTCM blowing up) was “required reading” at his firm.9

Kernen, with condescension, quipped: “I bet it is.” He then went on to ask Harding if he could provide some of his best “picks.” That question makes perfect sense for every fundamental trader who thinks he can predict the future, but it is a ridiculous question to ask a trend following trader. Harding replied that he could not forecast markets: “I can’t give you best picks.” He pointed out that his success comes from having a slight edge and proper betting.10

Kernen, still not about to acknowledge anything positive about trend following, smugly asked if Harding would know when the party was over. Harding was nonplussed, noting that there has been a long history of successful trend following going back 40 years. He also compared 2010-2011’s great trending markets to another era—the 1970s.11

Kernen, with little journalistic objectivity, shot back that he had heard those kinds of expressions before: “‘Please let there be another real estate boom because I spent all the money I made.’ I heard commodities guys saying that for a while [too].” He then wrapped up with standard pleasantries and one last zinger hoping that Harding could come back again “with the same moniker [and] same title.”12

Before analyzing the interview, consider a definition of critical thinking:

“Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness.”13

With that in mind, here are some questions to ponder:

1. Is it believable that Joe Kernen, the anchor of CNBC’s longest running program, had no knowledge and/or comprehension of trend following, or other descriptions of it such as managed futures or CTAs? If he was forced to raise his right hand under the threat of perjury, do you think he would still have such a limited understanding of trend following and managed futures?

2. When Kernen asked about trend followers purportedly pushing markets further than they should be fundamentally, did that mean he had a way to determine the correct price level of all markets at all times?

3. When Kernen brought up Long Term Capital Management in attempt to compare Harding to its demise, did he not understand that Harding did not believe in efficient markets? Had he ever looked at a monthly up and down track record of Harding or any trend follower?

4. Why ask a trend following trader for “picks”?

5. When Kernen asked Harding if he would come back with the same moniker and title, was he implying that he believed Harding would blow up soon and be back on CNBC under some reformulated firm name—like what the proprietors of Long Term Capital Management did after their blowup? Has he ever asked Warren Buffett that question?

I can easily see some painting this interview differently:

“Harding set himself up for the LTCM tie-in by framing himself as a computer science shop looking at data and being black box.”

“You have to expect Kernen to kick you. That’s what he does. Just like you know what you’re going to get from Glenn Beck or Stephen Colbert.”

“Harding basically says, ‘We are the smartest guys on the planet, trends work, and we look at a lot of data.'”

One reader, a reader who runs a fundamental advisory service, wrote me:

“Whether Kernen’s questions were clueless or not is really irrelevant. He did not argue with Harding on any point, and he gave Harding a good opportunity (within the time available) to explain how his firm implements trend following. [Kernen] was an ‘adult in the room.’ I’m thinking that’s the way serious trend followers ought to consider presenting themselves instead of sarcasm and ‘we don’t predict’ as if that is an obvious answer to any question.”

The evidence does not bear those criticisms out. There is a deeper game at play beyond my questions. Joe Kernen is not devoid of academic intelligence. He holds a bachelor’s degree from the University of Colorado in molecular, cellular, and developmental biology and master’s degree from Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He worked at several investment banks including Merrill Lynch.

I am no Harding fanboy or apologist, but I have spent time with him. That research time, coupled with his public career and track record, make him one of the most learned trend trading voices of the past twenty years. It is clear to me that Kernen had a pre-formulated agenda. His questioning was a transparent attempt to marginalize Harding and trend following. Why would Kernen do that? Imagine if the interview started like this:

“We at CNBC believe in efficient markets and the use of fundamental analysis. Our business model requires viewers to watch. Today, we have a guest on who has made billions with trend following trading, which does not require fundamental analysis or CNBC. Would you like to know how to make money without ever watching our channel again? Welcome David Harding!”

A Kernen ego will never debate this subject on neutral grounds, but that is no surprise. Learn from this interview and the analysis. For those with their eyes wide open, this is yet another moneymaking confidence builder.

Note: The unabridged interview can be found here. The footnotes are in my book Trend Commandments. A few years later Kernen interviewed Harding for a second time. I questioned him on Twitter and got blocked.

My Experience with Maria Bartiromo

My film ended up with Maria Bartiromo in it… in an unusual way:

Note: Trend followers trade everything: stocks, futures, currencies, LEAPs®, ETFs & commodities. Trend following is a strategy not limited to some one group of markets. And back to the main point of this page–my film rips news in half.