A successful trend following trader recently emailed:

It’s very hard to embrace diversification, especially without a systematic trend following portfolio scheme, when you are being frequently compared to the S&P and other indices. How can you convince your bosses that it’s okay to “underperform” when it’s due to diversification. Everyone sees the S&P as a minimum ROR, you are missing out if you make less no matter what the reason.

He goes on to send me this article by Randall Smith, “Pressure for High Marks at Harvard Extends to Its Investment Chief”:

The chief investment officer of the Yale endowment, David F. Swensen, set the bar for universities starting in 1988 when he created a widely imitated blueprint for high-octane investment returns with heavy doses of private equity and other alternatives to stocks and bonds.

Then from 1990 to 2005, Jack Meyer of Harvard gave Yale a run for its money with a streak of returns almost as sizzling, achieved by a team of swashbuckling in-house traders whose sky-high pay eventually led to their departures after an outcry from faculty and alumni.

But over the last decade, miscues by university management and more tepid investment returns have pulled down Harvard’s results, culminating in the June resignation of Jane L. Mendillo, the chief executive of the Harvard Management Company, who started just before the market collapse in July 2008.

The performance of Ms. Mendillo, who is leaving at the end of the year, illustrates not only the vicissitudes of investing but also the revolving-door aspect of an operation like the Harvard endowment, where retaining top talent can be difficult because of the intense scrutiny and the availability of bigger paychecks elsewhere.

“The pressure on people in that kind of institution is tremendous from people who want to see good results all the time,” said Keith Ambachtsheer, who runs an education program for nonprofit board members at the University of Toronto. “There’s no patience for the fact that managing endowments is a long-horizon enterprise that naturally involves occasional periods of disappointing results.”

Harvard expects endowment investment returns of about 15 percent for the year ended in June.

Harvard officials defend Ms. Mendillo’s record, saying that over the five years ended in June, the university’s endowment, the nation’s largest at $32.7 billion, matched its long-term record of 11 to 12 percent annual returns. They add that Ms. Mendillo coped well with multiple challenges during the financial crisis and stabilized the organization. And this month, Harvard is expected to report a return of about 15 percent for the year ended in June, the second-best of Ms. Mendillo’s term.

In three of the five Mendillo years for which Harvard and its Ivy League rivals have reported detailed results, however, as well as for the five years ended in June 2013, its endowment trailed all seven other Ivies. Including a steep 27.3 percent decline during the market collapse year, its five-year return was just 1.7 percent, compared with an average of 4.2 percent for the others.

“Their performance was not very good,” said Charles Skorina, a San Francisco endowment recruiter who calculated the five-year Ivy returns.

Results were all the more disappointing, he added, because Harvard pays “top dollar” for an in-house staff that invests about 40 percent of the assets, including $4.8 million for Ms. Mendillo in 2012, and $7.9 million and $6.6 million for her two highest-earning deputies. Other Ivies farm out most of their investments to outside managers and do not generally award such lavish paychecks.

In a letter sent last month to Harvard’s president, Drew Faust, a group of nine Harvard alumni renewed its past criticism of the pay for the endowment’s staff, noting that the total for 2013 of $132.8 million had doubled in the previous four years. ”

Harvard officials say the higher pay levels reflect Ms. Mendillo’s efforts to rebuild the staff, which had been depleted by the departures of numerous top traders, and the exceeding of certain benchmarks.

Some associates of Ms. Mendillo, who came up through the ranks at Harvard and then led both the Wellesley and Harvard endowments, say she acknowledged unhappiness with the scrutiny on Harvard’s returns. “She didn’t like it; she is a very private person and doesn’t seek the spotlight. So the negative focus on absolute returns did bother her,” said Verne O. Sedlacek, chief executive of Commonfund, which manages $25 billion for nonprofit groups. Mr. Sedlacek worked with Ms. Mendillo, 56, at the Harvard endowment for a decade. Harvard officials declined to comment beyond a brief statement applauding the latest five-year returns as a “strong recovery.”

One former official of Harvard Management compared the endowment’s cautious, defensive style in the Mendillo years to a soccer team that tries to keep possession of the ball instead of taking shots on goal. Many of the company’s alumni called Ms. Mendillo more of a steady, capable manager than a visionary investor.

Returns in the first of the cellar years, ended in June 2009, were weighed down by the need to sell illiquid assets at a discount to produce cash for the university, as well as a decline of more than 50 percent in the endowment’s real estate holdings — roughly double the decline of the United States stock market. But former Harvard endowment employees say returns in the other bottom-ranked years ended in June 2012 and 2013 were held back by less obvious factors like holding too few publicly traded United States stocks, which shot up 12.2 percent annually in those two years, and placing too big a bet on emerging stock markets, where Harvard underperformed market indexes that themselves produced annual losses of 6.7 percent.

Another drag during the five-year period ended June 2013 were “real assets,” including real estate, natural resources and commodities, where Ms. Mendillo kept the weighting at as much as 25 percent — higher than most other Ivies — which produced losses of 3.6 percent annually, held back by low inflation.

Her best sector was fixed income. As initially reported, it returned an average annual 4.8 percent, beating Harvard’s own benchmark of 2.8 percent, while trailing a more widely used index, BarclaysU.S. Aggregate, which gained 5.2 percent. Harvard says it actually beat the Barclays index with a 6.1 percent return because it retroactively removed high-yield securities from the category after it incurred steep losses in 2009.

Mr. Meyer’s successor, Mohamed A. El-Erian, who arrived in February 2006 and left after only 21 months for what he said were family reasons, posted a return of 23 percent during his lone full year ended June 2007, aided by a 44 percent bounce in emerging markets and a surge in commodities.

Friends say Ms. Mendillo is looking forward to escaping the pressure cooker, where criticism of the recent results may have made it tougher for her to lead and retain top talent. For example, after the longtime head of private equity, Peter Dolan, resigned last year, his successor, Lane MacDonald, abruptly departed in February after just a few months in the job to manage a family office for the Johnson family, which owns a stake in Fidelity Investments.

Lawrence E. Golub, a Harvard alumnus whose Golub Capital lends to midsize companies, said Ms. Mendillo did “a great job” steering Harvard through the crisis and revamping its risk and liquidity profile. But he noted that the job required three separate skills in investing, managing and dealing with Harvard’s various “constituents and interest groups.” He added, “Any job with those challenges, that’s a very tiring job.”

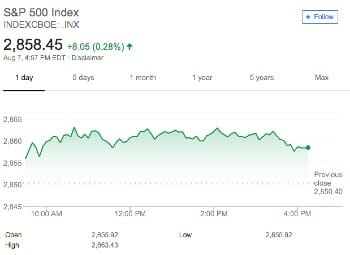

It’s also worth noting what the S&P really represents today for folks like at Harvard fund management. It represents government policy. So trust the S&P, you trust the government.

Trend following just ignores it all.

Other Reader Questions, Feedback, and useful Content

What is the best Entry System for Trend Following?

Never Ending Social Security Drama

How can you move forward immediately to Trend Following profits? My books and my Flagship Course and Systems are trusted options by clients in 70+ countries.

Also jump in:

• Trend Following Podcast Guests

• Frequently Asked Questions

• Performance

• Research

• Markets to Trade

• Crisis Times

• Trading Technology

• About Us

Trend Following is for beginners, students and pros in all countries. This is not day trading 5-minute bars, prediction or analyzing fundamentals–it’s Trend Following.